Sunday, July 25, 2021

Diane's 35th birthday

Monday, July 19, 2021

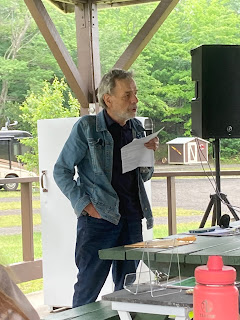

My Dad's speech at the Newport Vets Town Hall, 2021

Hello, my name is Rod Auclair. I'll be 82 two months from today, and I find that the real pleasure and treasure of being elderly are our memories.

God knows, we don't have a lot of time left to make new ones. "Young men shall dream vision and old men shall dream dreams," it says somewhere in the Bible. And some of my best memories came from the beginning of my service in the U.S. Air Force in January, 1962 in enlisted men's basic training at Lockland AFB, San Antonio, to its end as a captain at Stewart AFB in Newburgh, NY in Dec, 1966. Four months before our son, Douglas, was born, his crib, a dresser drawer on a 3rd floor walking opposite the police station on 77 Ann St., Newsburgh.

I started as a weapons controller, better understood as a defense fighter aircraft interceptor director in a 4 story block house, two stories of which housed our giant IBM 2000 computer, no chips then, only very hot and very many glass radio tubes that were our 0101 on/off computing switches. And it worked and we watched those antique fighters (and their pilots) that you once could see lined up outside the gate of Vermont's ANG (Air National Guard) at Burlington, the tubby F-89 Scorpion, the Delta winged darts of the F-102 and F-106, the fantastic F-16. I was a gold bar 2nd Looey then, and learning to direct fighter pilots with no flight experience myself was stressful and scary, but I remember the smile and congratulations from a Korean War vet captain who patted me on the shoulder and said, "Congratulations, Auclair, you got your first [vulgar word deleted] when I and my younger airman ?/c guided a real fighter to attack a real mark inwards, probably a T-80 Korean war vintage Shooting Star.

The affirmation from that good-hearted captain, the lasting affect of what affirmation must mean to all of us. That we had worth, that we have done, and can do, well. This was something special that I found in my military service, for more than in civilian life. And I would find it so even more when I was puzzled to find I was assigned to a year's remote tour to Thule, Greenland, after I had asked for duty in West Germany. THULY? UltimaTule? which translates roughly to "the end of the world."

We were a special squadron, given the task of "bluesuiting" [militarizing] the operations control center of the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System, ironically acronymed "BMEWS"ed, which it wasn't. We would take over from very highly paid RCA contract people to run the monster radar arrays out there, away from the seaport airbase of Thule, formerly the home of Inuit Native Greenlanders who were moved across the icy bay, our whole base including us out in booneys, powered by generators and steam from a permanently moored WWII Liberty Ship.

But the magic was I served with officers and enlisted men who were WWII-Army Air Corps (brown shoe) vets called back to duty for the "Korean" police action of the fifties, who decided – what the hell! – might as well get my 20 [years of service] and retire, courtesy of Uncle Sam. And they (mostly) were a hoot! They had this perspective of "you gotta be kidding" to razing each other by making midnight phone calls (when it was our shift cycles) to their buddies asleep back in the BOQ as the 2th clk, GMT.

11:11 "TOOTHPICKS!" or 22:22 hrs "TRAIN TIME! [too-too:too-too!]"

Your tax dollars at work.

But the most exciting moment was when Major Lynn F. Walker, Senior Space Surveillance Officer and I, his assistant officer on duty in Ops with our enlisted crew, headed by a very competent and calm Senior M. Sgt, picked up what looked like bogies [missile] coming in our only, huge scanning radar which was about 4 stories high and groaned like one of monster dinos from Jurassic Park. when it moved and locked onto a threat. Alarms went off from Greenland to North American Air Defense Command (NORAD) in Atom Bomb-proof control center mounted on giant springs in Cheyenne Mountain, Colorado Springs. The system console that controlled this radar (alarm lights flashing) to use that the lunar cancellation switch had not been thrown. We were tracking the moon! Sarge reached up and flicked the switch and all became quiet, except for the dripping sweat.

Major Walker and I remained friends for the few short years he lived after he retired. He was so often homesick for his wife at Thule. His wife was Catholic, and he became so also at Thule, and I, half his age, was honored to be his God Father.

My Mom's Letter to my Dad, ... on my Birthday

Sunday, July 18, 2021

The Military (Combined post)

Comrades-in-arms

Saturday, July 17, 2021

Thank you for your Service

Wednesday, June 16, 2021

ἥρως

The ancient Greek word for 'a man' is 'ἥρως' ('hero').

And, ... men are heroic, stoic ones at that. (Although the ladies may argue that a man with a cold is nothing like a stoic hero). But we're also supposed to 'open up.' We're supposed to share our thoughts and feelings. Because that builds better relationships and happier families.

But does it? Where does this advice come from, because, it seems to me, that this is a modern invention, and not tested with ... well, not tested at all, by any measure, other than a 'well, that's what you're supposed to do.'

But are we?

I had a twinge today, over my heart.

So, the modern approach would be to share this with my family. But I know what would come from that: we would rush to the ER, the ER would rush me through tests, the doctor would review the tests and, like every other time (even when I had my heart attack), the doctor would see every single indicator in the nominal range, but, the doctor, being a doctor under modern liability constraints, would recommend I convalesce at the hospital under 24-hour observation.

A visit to the ER costs $2400 if I'm driven there (more if I'm escorted in an ambulance) (much more). An overnight stay at the hospital?

I don't even want to think about that cost.

So, instead of baring my heart and sharing my feelings, I went for a walk.

Yeah. Like a man, I decided to walk it off.

And that worked.

This time.

But what if it didn't?

Well, the first time I decided to run my heart attack off, that didn't work, and I almost died (twice) and was rushed to the ER, WHO FOUND ABSOLUTELY NOTHING WRONG WITH ME, until I ended up on the operating table with a stent.

Yay.

So, either way, walking it off worked. And, even when it didn't, I turned around, came back home, told my family, and we rushed to the hospital WHO SAID NOTHING WAS WRONG WITH ME because they're used to the modern man, who eats junk food, doesn't exercise, and dies in a very obvious way, not with a guy who exercises every day and whose body adjusts around bad genetics.

What does it profit my family that I share with them 'I have a twinge over my heart'?

The profit, actually, the cost, is that they worry unto death, all day, waiting, again, for a no-result from the hospital and a $2400 bill for the trouble.

Men, ... women, too: be a burden on your families, that's what God put you on this good, green Earth for, to help each other make your way through this day. You can't help, nor be a help, if you have to do everything all by yourself. If the world hinges on you, alone, then what, even, is every other person in your life for? Each person in your life is a gift from God. Thank God for these gifts by being there for them and allowing them to be there for you.

But don't be an unnecessary burden. Don't impose yourself onto people. Don't smother them, don't worry them, don't crush them out of the one-sided conversation you harangue them with. You are here for them which means if you have a plan or a problem, include them in helping to solve it, if you have a worry, share it, but only insofar as they can help you get over it.

Fine line?

Nope. You know when you're being a jerk.

Don't be a jerk to your family. Be their help, and be their hope.